BBC

BBC“I don’t need to be right here in any respect” is a protestation you’ll anticipate to listen to from somebody in jail. But, as she sits in her maroon overalls, Tetyana Potapenko is adamant that she is just not who the Ukrainian state says she is.

One 12 months right into a five-year sentence, she is one in every of 62 convicted collaborators on this jail, held in isolation from different inmates.

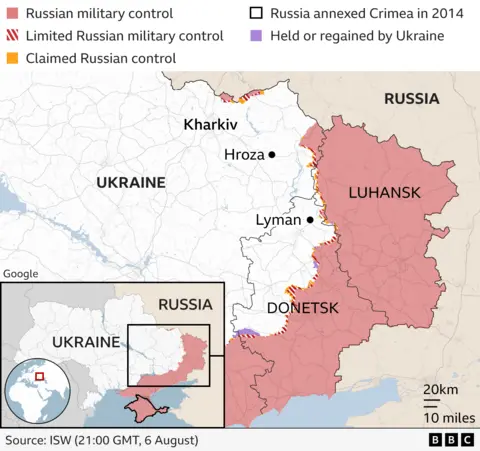

The jail is close to Dnipro, about 300km (186 miles) from Tetyana’s dwelling city of Lyman. Close to the entrance traces of the Donbas, Lyman was occupied for six months by Russia and liberated in 2022.

As we sit within the pink-walled room the place inmates can cellphone dwelling, Tetyana explains that she had been a neighbourhood volunteer for 15 years, liaising with native officers – however that carrying on these duties as soon as the Russians arrived had price her dearly.

Ukrainian prosecutors claimed she had illegally taken an official function with the occupiers, which included handing out aid provides.

“Winter was over, individuals had been out of meals, somebody needed to advocate,” she says. “I couldn’t go away these outdated individuals. I grew up amongst them.”

The 54-year-old is one in every of virtually 2,000 individuals convicted of collaborating with the Russians underneath laws drafted practically as shortly as Moscow’s advance in 2022.

Kyiv knew it needed to deter individuals from each sympathising and co-operating with the invaders.

And so, in a little bit over every week, MPs handed an modification to the Criminal Code, making collaboration an offence – one thing they’d didn’t agree on since 2014, when Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimean peninsula.

Before the full-scale invasion, Tetyana used to liaise with native officers to offer her neighbours with supplies equivalent to firewood.

Once the brand new Russian rulers had been in place, she says she was satisfied by a good friend to additionally have interaction with them to safe much-needed medicines.

“I didn’t co-operate with them voluntarily,” she says. “I defined disabled individuals couldn’t entry the medication they wanted. Someone filmed me and posted it on-line, and Ukrainian prosecutors used it to say I used to be working for them.”

After Lyman was liberated, a courtroom was proven paperwork she had signed that advised she had taken an official function with the occupying authority.

She immediately turns into animated.

“What’s my crime? Fighting for my individuals?” she asks. “I by no means labored for the Russians. I survived and now discover myself in jail.”

The 2022 collaboration legislation was drawn as much as stop individuals from serving to the advancing Russian military, explains Onysiya Syniuk, a authorized skilled on the Zmina Human Rights Centre in Kyiv.

“However, the laws encompasses all types of actions, together with these which don’t hurt nationwide safety,” she says.

Collaboration offences vary from merely denying the illegality of Russia’s invasion, or supporting it in particular person or on-line, to taking part in a political or army function for the occupying powers.

Accompanying punishments are robust too, with jail phrases of as much as 15 years.

Out of just about 9,000 collaboration instances to this point, Ms Syniuk and her staff have analysed a lot of the convictions, together with Tetyana’s, and say they’re involved the laws is just too broad.

“Now people who find themselves offering very important companies within the occupied territories can even fall liable underneath this laws,” says Ms Syniuk.

She thinks lawmakers ought to take note of the fact of residing and dealing underneath occupation for greater than two years.

We drive to Tetyana’s dwelling city to go to her frail husband and disabled son. As we close to Lyman, the scars of conflict are clear.

Civilian life drains away and automobiles steadily flip a army inexperienced. Droopy energy traces cling from collapsed pylons and the principle railway has been swallowed by overgrown grass.

While the sunflower fields are unscathed, the city isn’t. It has been bludgeoned by airstrikes and combating.

The Russians have now moved again to inside practically 10km (6 miles). We had been instructed they often begin shelling at about 15:30, and the day we visited was no exception.

Tetyana’s husband, Volodymyr Andreyev, 73, tells me he’s “in a gap” – the family is falling aside with out his spouse, and he and his son solely handle with the assistance of neighbours.

“If I had been weak, I’d burst into tears,” he says.

He struggles to grasp why his spouse is just not with him.

Tetyana might need obtained a shorter sentence had she admitted her guilt, however she refuses. “I’ll by no means admit that I’m an enemy of state,” she says.

But there have been enemies of state – and their actions have had lethal penalties.

Last autumn, we walked on the bloodstained soil of the liberated village Hroza within the Kharkiv area of jap Ukraine. A Russian missile had hit a restaurant the place the funeral of a Ukrainian soldier was going down – it had been unimaginable to carry the service whereas Hroza was underneath Russian occupation.

Fifty-nine individuals – virtually 1 / 4 of Hroza’s inhabitants – had been killed. We knocked on doorways to search out youngsters alone at dwelling. Their mother and father weren’t coming again.

The safety service later revealed that two native males, Volodymyr and Dmytro Mamon, had tipped off the Russians.

The brothers had been former law enforcement officials who had allegedly begun working for the occupying pressure.

When the village was liberated they fled throughout the border with Russian troops, however stayed in contact with their outdated neighbours – who unwittingly instructed them in regards to the upcoming funeral.

YAKIV LIASHENKO/EPA-EFE/REX

YAKIV LIASHENKO/EPA-EFE/REXThe brothers have since been charged with excessive treason – however are unlikely to be jailed in Ukraine.

That is broadly the story of Kyiv’s battle with collaborators. Those who commit extra critical crimes – guiding assaults, leaking army info or organising sham referendums to legitimise occupying forces – are principally tried in absentia.

Those going through much less critical prices are sometimes those who find yourself within the dock.

Under the Geneva Convention, occupying Russian forces have to permit and supply the means for individuals to proceed residing their lives.

Just as Tetyana Potapenko says she tried to do, when troops moved into Lyman in May 2022.

Her case is one in every of a number of we’ve uncovered throughout jap Ukraine.

They embody a faculty principal jailed for accepting a Russian curriculum – his defence, his lawyer says, was that though he had accepted Russian supplies, he didn’t use them. And within the Kharkiv area, we heard a few sports activities stadium supervisor going through 12 years in jail for persevering with to host matches whereas underneath occupation. His lawyer says he had solely organised two pleasant matches between native groups.

In the eyes of the United Nations (UN), these collaboration convictions breach worldwide humanitarian legislation. A 3rd of these handed down in Ukraine from the beginning of the conflict in February 2022 till the top of 2023 lacked a authorized foundation, it says.

“Crimes have been carried out on occupied territory, and folks have to be held to account for the hurt they’ve completed to Ukraine – however we’ve additionally seen the legislation utilized unfairly,” says Danielle Bell, the top of the UN’s Human Rights Monitoring Mission within the nation.

Ms Bell argues that the legislation doesn’t contemplate somebody’s motive, equivalent to whether or not they’re actively collaborating, or making an attempt to earn an revenue, which they’re legally allowed to do. She says everyone seems to be criminalised underneath its imprecise wording.

“There are numerous examples the place individuals have acted underneath duress and carried out features to easily survive,” she says.

This is precisely what occurred to Dmytro Herasymenko, who’s from Tetyana’s dwelling city of Lyman.

In October 2022, he emerged from his basement after artillery and mortar fireplace had subsided. The entrance line had handed via Lyman, and it was underneath Russian occupation.

“By that point individuals had been residing with out energy for 2 months,” he recollects. Dmytro had labored as an electrician within the city for 10 years.

The occupying authorities requested for volunteers to assist restore energy, and he caught up his hand. “People needed to survive,” he says. “[The Russians] stated I might work like this or in no way. I used to be afraid of turning them down and being hunted by them.”

For Dmytro and Tetyana, the aid of liberation was temporary. After Ukraine took again management of the city, officers from the nation’s safety service – the SBU – introduced them in for questioning.

After admitting to having supplied energy to the Russian occupiers, Dmytro was swiftly handed a suspended sentence and banned from working as a state electrician for 12 years.

We discovered him on the storage the place he now works as a mechanic. Shiny instruments replicate his enforced profession change. “I can’t be judged in the identical method as collaborators who assist information missiles,” he says.

His protests echoed Tetyana’s. “What can you are feeling when a overseas military strikes in?” she requested. “Fear in fact.”

Such worry is justified. The UN has discovered proof of Russian forces concentrating on and even torturing individuals supporting Ukraine.

“We’ve had instances of people being detained, tortured, disappeared, merely for expressing pro-Ukrainian views,” says the UN’s Ms Bell.

From the second Moscow invaded Crimea in 2014, the definition of being “pro-Russian” modified within the eyes of Ukrainian lawmakers – from merely favouring nearer nationwide ties, to supporting a Russian invasion seen as genocidal.

That similar 12 months, Russian proxy forces – funded by the Kremlin – additionally occupied a 3rd of the Donetsk and Luhansk areas.

It is commonly the aged who select to, or are pressured to, stay underneath occupation. Some could also be too frail to depart.

There can even be these with Soviet nostalgia or sympathy with modern-day Russia.

But given how Ukraine may in the future should reunite, does the collaboration legislation come down too arduous?

The message from one MP who helped draw it up is blunt: “You’re both with us, or in opposition to us.”

Andriy Osadchuk is the deputy head of the parliamentary committee on legislation enforcement. He strongly disagrees that the laws breaks the Geneva Convention, however accepts it wants enchancment.

“The penalties are extraordinarily robust, however this isn’t a daily crime. We are speaking about life and dying,” he says defiantly.

Mr Osadchuk believes it’s, in reality, worldwide legislation which has to meet up with the conflict in Ukraine, not the opposite method spherical.

“We have to construct Ukraine on liberated territories, and never make somebody completely happy from the skin world,” he says.

The UN monitoring mission admits there have been some enhancements. Ukraine’s prosecutor common has just lately instructed his workplaces to adjust to worldwide humanitarian legislation whereas investigating collaboration instances.

Ukraine’s parliament can be planning so as to add extra amendments to the laws in September. One advised change would see some individuals issued with fines as an alternative of jail sentences.

For now, Kyiv sees the likes of Tetyana and Dmytro as acceptable recipients of robust justice, if it means Ukraine can lastly be freed from Russia’s grasp.

The pair declare they solely remorse not escaping when the Russians moved within the first time.

But with the state respiratory down their necks and Lyman vulnerable to falling as soon as extra, it’s not clear how candid they are often.

Additional reporting by Hanna Chornous, Aamir Peerzada and Hanna Tsyba.

All BBC photos by Lee Durant.