BBC

BBCOne of the worst droughts in dwelling reminiscence is sweeping throughout southern Africa, leaving near 70 million individuals with out sufficient meals and water.

In Mudzi district in northern Zimbabwe, a group and their livestock are gathered on a bone-dry riverbed. The Vombozi usually flows all year long however proper now, it’s simply beige sand so far as the attention can see.

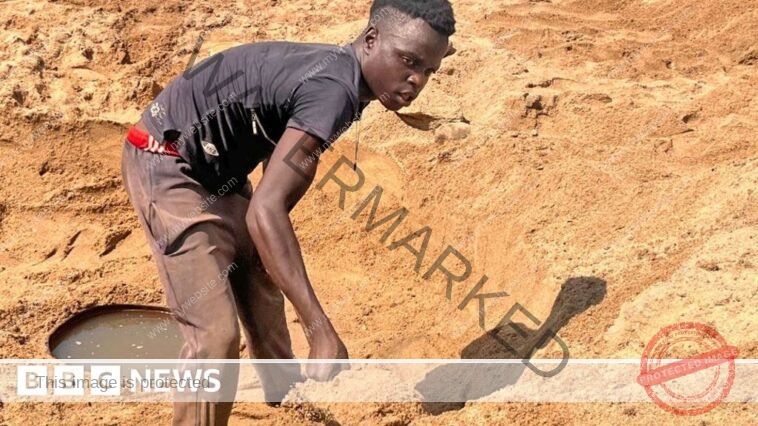

Armed with shovels and buckets, the lads are digging into the river flooring, desperately making an attempt to extract the final drops of water from it.

Rivers and dams have dried up in different components of the district and in consequence an increasing number of individuals are descending on this particular riverbed in Kurima village, placing stress on the water supply.

Along the riverbed are a number of holes, massive sufficient to suit a single bucket.

Children are bathing, girls are doing laundry and giving their bellowing cattle drinks of water.

Gracious Phiri, a mom of 5, stands amongst these girls. The 43-year-old tells the BBC she now has to stroll additional than typical, spending three hours on daily basis travelling to fetch water.

Ms Phiri lowers her bucket into the half-metre (19in) huge gap and attracts brown-coloured water. She worries about her household getting sick.

“As you possibly can see, the cattle are consuming from the identical pit as us. Their urine is correct there… it isn’t very wholesome,” she says.

“I’ve by no means seen something like this.”

Food can also be briefly provide in Zimbabwe the place 7.7 million individuals face starvation. In Mudzi the variety of households who’ve entry to a ample quantity of reasonably priced, nutritious meals has dropped by greater than half in comparison with earlier years, the native well being authority says.

Children have been significantly impacted – since June hospital admissions for children with average to extreme malnutrition have doubled.

A village feeding programme is making an attempt to sort out the issue. Once per week girls in the neighborhood collect, bringing no matter produce they’ve in an effort to contribute to a porridge for underneath fives.

Ground baobab fruit, peanut butter, milk and leafy inexperienced greens are stirred into the porridge so as to add additional vitamins.

But the record of components shrinks each week – cow-peas and beans lately grew to become unavailable due to the poor harvests.

The authorities, with the assist of companions just like the UN kids’s company, Unicef, devised the village feeding scheme and it used to run at the least 3 times per week.

“But due to the El Niño drought we at the moment are solely giving it as soon as per week,” explains Kudzai Madamombe, Mudzi district’s medical officer.

“Because the rains didn’t come, we suffered a 100% loss when it comes to all of the crop,” he provides, saying the programme is likely to be pressured to cease altogether within the subsequent month as meals shares dwindle.

Clinics offering Zimbabweans in Mudzi with important healthcare have additionally been affected – boreholes that provide 1 / 4 of clinics within the district with water have run dry, Mr Madamombe says.

And the foremost dam within the district has solely a month’s provide of water left.

As a outcome vegetable irrigation schemes, together with one which supported 200 native farmers, have been suspended.

The distress is all over the place. Tambudzai Mahachi, 36, says she planted acres of maize, cow-peas and peanuts on her plot.

For all her arduous work, she bought nothing in any respect, not even a plate of meals. Even her hardy baobab tree produced hardly any fruit.

In a very good yr Ms Mahachi says she would usually provide markets within the capital, Harare, however she is now among the many hundreds of thousands of Zimbabweans counting on handouts.

While the village feeding scheme offers meals at some point of the week, her kids must eat on daily basis.

Seated in a thatched hut, she boils wheat so she will present her two kids with breakfast. The wheat was equipped by a charitable neighbour.

“We have gone from consuming what we would like and once we need to limiting meals,” Ms Mahachi says.

“The older lady understands that we typically can solely have porridge. But at instances I can see that my youngest is hungry.”

The rains failed in most of southern Africa this yr, on a continent the place a lot of the agriculture depends on rainfall, fairly than irrigation, for water.

The drought has prompted a few third of the international locations in southern African to declare a state of catastrophe. A large 68 million individuals throughout the area want meals support.

The Southern African Development Community (Sadc) – a grouping of nations within the area – appealed for $5.5bn (£4bn) in support to fight the results of drought in May. So far, solely a tiny fraction has been acquired.

“If you go wherever in southern Africa, household granaries are empty, and maize, which is the area’s most consumed when it comes to carbohydrates, is now priced out of many individuals’s palms,” Tomson Phiri, southern African spokesperson for the UN World Food Programme (WFP), tells the BBC.

“The state of affairs is barely going to worsen.”

The WFP has solely acquired one fifth of the $400m its wants for emergency help, he says, including that southern Africa is experiencing its largest deficit in maize in 15 years.

And the starvation and water disaster is but to peak – October, the most well liked and driest month of the yr, remains to be a good distance off.

If rain falls in November or December, which is when the wet season sometimes begins, farmers should wait till March to reap maize.

It is one thing Ms Mahachi is conscious about as she cracks open some wild fruit to stave off her starvation pangs, uncertain about what lies forward within the coming months for her younger household.

You may additionally be desirous about:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC